Learn more about a Ukrainian vyshyvanka, its importance to the Ukrainians, and how an embroidered shirt has got itself a holiday in Ukraine

When developing sophisticated custom software solutions, engineers handpick the technologies and frameworks that would help that will work best for a particular solution. For example, JavaScript (with all its libraries) is one of the best frontend programming languages; meanwhile, PHP or .NET work incredibly well in backend development. Knowing the code within the solution makes it easier for the engineers to keep it stable, running, and scalable.A nation that cherishes its traditions is similar to a team of engineers taking the utmost care of their code. Knowing, understanding, and honoring one’s history makes it easier to build a brighter future – just like in customer software development. Moreover, it seems easier to deal with legacy code when it requires no updates but just needs proper maintenance and support. On every third Sunday of May, Ukraine celebrates Vyshyvanka Day, celebrating its versatile and saturated history embedded and reflected in the flamboyant ornaments masterfully scattered all over the cloth. With one of Nearshore Friends’ major delivery centers in Kyiv, we feel solemnly and pleasantly obliged to tell you more about the very concept of vyshyvanka and why it matters so much to the Ukrainians.  More Than Clothes: What Is a Vyshyvanka? Embedded into a white cloth, a stretch of colorful thread ornaments is indeed the original Ukrainian code, as it preserves the country’s history and customs and even mirrors its splendid nature. As you might have already guessed, vyshyvanka is a national Ukrainian embroidered shirt. The very word “vyshyvanka” is a noun derivative from a Ukrainian verb “вишива́ти” (vyshyvaty, to embroider). Just like the Ukrainian language has loaned such lexemes as the kilt, moccasins, jumper, etc., the English language has adopted vyshyvanka and now uses it as a loanword. An embroidered shirt has been a part of the Ukrainian identity since the break of dawn. The archeological data claims that vyshyvanka dated back to V-III centuries B.C. and was a creation of Scythian fine art – remnants of woolen clothes with small embroidery patches were found in the graves of that time. A later proof of embroidery having had been an indispensable part of the Kyivan Rus’ and then Ukraine’s life can be found in the original murals in the famous Saint Sofia Cathedral in Kyiv, the construction of which was initiated in 1037 by Yaroslav the Wise, the Great Prince of Kyiv. Nowadays, each of the 25 Ukrainian regions, including Crimea, has its own vyshyvanka style. A renowned anthropologist J.J. Curga claims in his work Echoes of the Past: Ukrainian Poetic Cinema and the Experiential Ethnographic Mode: “The vyshyvanka not only speaks of its Ukrainian origin but also of the particular region it comes from. The knowing eye could detect where a person hailed from by the clothes on their back. Thus, embroidery is an important craft within Ukraine, and different techniques exist to suit local styles with particular patterns and colors.” Vyshyvanka is definitely a code of Ukrainian identity. Even though its code pieces may come from different repositories, look different, and convey various messages, it is undoubtedly a monolith infrastructure, not a set of microservices.Interesting Facts about Vyshyvanka Before we move on to talking about Vyshyvanka Day, here are ten interesting facts about vyshyvankas that might help you grasp the context of the celebration.

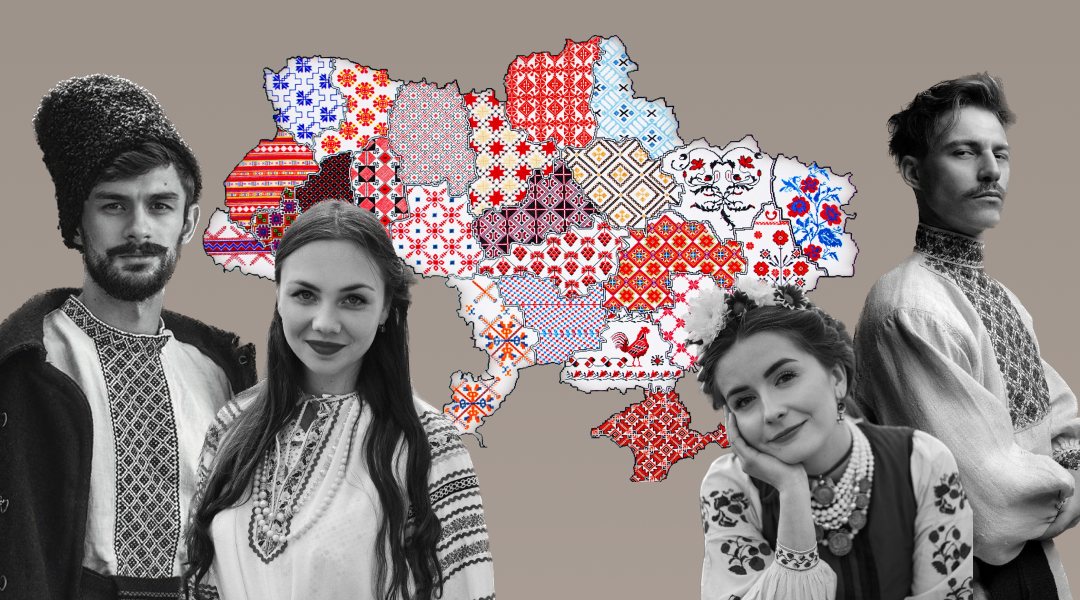

More Than Clothes: What Is a Vyshyvanka? Embedded into a white cloth, a stretch of colorful thread ornaments is indeed the original Ukrainian code, as it preserves the country’s history and customs and even mirrors its splendid nature. As you might have already guessed, vyshyvanka is a national Ukrainian embroidered shirt. The very word “vyshyvanka” is a noun derivative from a Ukrainian verb “вишива́ти” (vyshyvaty, to embroider). Just like the Ukrainian language has loaned such lexemes as the kilt, moccasins, jumper, etc., the English language has adopted vyshyvanka and now uses it as a loanword. An embroidered shirt has been a part of the Ukrainian identity since the break of dawn. The archeological data claims that vyshyvanka dated back to V-III centuries B.C. and was a creation of Scythian fine art – remnants of woolen clothes with small embroidery patches were found in the graves of that time. A later proof of embroidery having had been an indispensable part of the Kyivan Rus’ and then Ukraine’s life can be found in the original murals in the famous Saint Sofia Cathedral in Kyiv, the construction of which was initiated in 1037 by Yaroslav the Wise, the Great Prince of Kyiv. Nowadays, each of the 25 Ukrainian regions, including Crimea, has its own vyshyvanka style. A renowned anthropologist J.J. Curga claims in his work Echoes of the Past: Ukrainian Poetic Cinema and the Experiential Ethnographic Mode: “The vyshyvanka not only speaks of its Ukrainian origin but also of the particular region it comes from. The knowing eye could detect where a person hailed from by the clothes on their back. Thus, embroidery is an important craft within Ukraine, and different techniques exist to suit local styles with particular patterns and colors.” Vyshyvanka is definitely a code of Ukrainian identity. Even though its code pieces may come from different repositories, look different, and convey various messages, it is undoubtedly a monolith infrastructure, not a set of microservices.Interesting Facts about Vyshyvanka Before we move on to talking about Vyshyvanka Day, here are ten interesting facts about vyshyvankas that might help you grasp the context of the celebration.

- It is a talisman.

Ukrainians perceive their vyshyvankas as talismans that protect the people wearing them. It is believed that these shirts have the power to help the ones wearing them dodge any harm coming their way. There is even a saying in Ukrainian, “Народився у вишиванці” (narodyvsia u vyshyvantsi) – literally translated as “he was born wearing a vyshyvanka”. The saying is used when pointing out a person’s ability to survive and thrive against the odds.

- An Austro-Hungarian archduke’s favorite.

There’s no wonder that the Ukrainians have had their own name for Wilhelm Franz von Habsburg-Lothringen, the Archduke of Austria. A great fan of the Ukrainian people, he loved Ukraine and everything related to it – vyshyvankas in particular – that the Ukrainian people called him Basil the Embroidered.

Wilhelm Franz von Habsburg-Lothringen wearing a vyshyvanka.

- It is not clothes for every day.

Holding their traditions in high regard, Ukrainian people would only wear vyshyvankas for special occasions, such as weddings, religious holidays (Christmas, Easter, etc.), birthdays, and less festive yet solemn events, such as funerals, commemoration days, etc.

- Special preparation is required.

It takes three years to prepare the special white threads for white-on-white vyshyvankas popular in the Poltava region (Central Ukraine).

- A worldwide celebration.

Vyshyvanka Day is celebrated in 60+ countries where there’s a Ukrainian diaspora.

- In unity with nature.

Initially, all the colored threads for vyshyvankas had been prepared using natural stains. For example, yellow and goldish hues would be the result of baking the thread in wheat bread.

- A global fashion trend.

Ukrainian embroidery has become a global fashion trend in the middle of the 2010s. One of the world’s leading fashion tabloids, Vogue, started writing about vyshyvankas permanently, focusing primarily on how they can be incorporated into the day-to-day street style of the Europeans.

- Preferred by Ukrainian nobility.

Ivan Franko and Taras Shevchenko – Ukraine’s greatest poets, writers, and thinkers of the 19th and 20th centuries, respectively, were big fans of vyshyvankas.

- A constellation of variations.

In general, black, red, and white are the primary colors used in a Ukrainian vyshyvanka, while yellow, green, and blue are considered supplementary. Regarding the ornaments, they can often reflect the local environment, featuring leaves, bark, flowers, berries, etc.

- We love it here at Nearshore Friends.

Vyshyvanka is a trend at Nearshore Friends. Our Chief Revenue Officer, Alphonsine Williams, proudly wore his vyshyvanka tothe NFL Honors awards show, where, together with his friends from the Ukrainian League of American Football, he had the honor to share the stories of the league’s players who have volunteered to defend their homeland against unprovoked Russian aggression and paid the ultimate price for the sake of freedom in Europe. Alphonsine Williams and friends wearing vyshyvankas at an NFL event What Is Vyshyvanka Day?As has already been mentioned, Vyshyvanka Day is celebrated every third Thursday of May. This year, it will be May 18. An international holiday celebrated in more than 60 countries around the world, including the United States, Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and France, Vyshyvanka Day aims to preserve Ukrainian folk traditions. Some might say the holiday boils down to specifically maintaining the tradition of creating and wearing ethnic embroidered clothes. Nonetheless, the value of vyshyvanka’s symbolism is way more far-reaching. The people of Ukraine consider vyshyvanka as one of the major totems of their national identity.Yet, for decades, everything that’s originally Ukrainian has been forbidden and blocked by the Soviets. The first years of Ukraine’s independence tolled on the nation’s civil consciousness with the economic hardships of the post-colonial aftermath. It was in 2006 that a Chernivtsi National University Student, Lesia Voroniuk came up with an idea to gather together with her fellow students on a chosen day and wear their vyshyvankas to the university. Their first try was a success: several dozen students and faculty members supported the idea; at least, they thought it was a success until they saw how the following year’s Vyshyvanka Day turned out.During 2007-2011, the holiday grew to a national level. The Ukrainian diaspora from all around the world joined. When choosing the date for the celebration, Lesia said that they had intentionally chosen a weekday to strike on the message that vyshyvanka is an integral component of modern Ukrainians’ lives and not a relic from the past. In 2011, on the holiday’s fifth anniversary, the participants set a Guinness World Record for “the largest number of people dressed in embroidered shirts and gathered in one place” – more than 4,000 people in their vyshyvankas gathered on the central square of the city of Chernivtsi. They even prepared one for the city’s university main building by sewing a gigantic (4 × 10 meters) vyshyvanka.In 2015, after the start of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of the Donbas and annexation of Crimea, Vyshyvanka Day was celebrated under the slogan: “Give a vyshyvanka to a defender.” As already mentioned, vyshyvanka is known as a talisman that protects people from anything bad that might happen to them, and the campaign above was meant to raise the Ukrainian army’s fighting spirit. That year, it was for the first time that more than 50 countries joined the celebrations. Eight years later, and almost 1.5 years into the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, vyshyvanka remains the unchanging symbol of the Ukrainian identity. During one of his latest addresses to the nation, President Volodymyr Zelenskyi wore a black vyshyvanka with green and olive embroidery featuring the emblem of the Kyivan Prince, Sviatoslav the Brave. Today’s Ukrainian Special Operations Forces use it as their symbol as well. Time passes, but vyshyvankas keep on reflecting and preserving everything that happens in Ukraine’s rich and yet swerving history.Closing RemarksVyshyvanka is more than just clothes for Ukrainians. As a cumulative term, vyshyvanka is a repository of nations codes, libraries, and frameworks, which together represent the Ukrainian culture in its magnitude of an already accomplished project; a project that happened and has a bright future in front of itself. While the Internet might still be full of ludicrous Russian propaganda’s narratives about the Ukrainians being the descendants of the Russians – cultural, political, economic – the very concept of vyshyvanka (so tiny in the greater scheme of things and yet so powerful in terms of establishing historical justice) eradicates this semantic nonsense. At the end of the day, the Kyivan Rus, was called Kyivan and not Moscowite for a reason. It is a pride for us to be able to say that our colleagues in Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, are joining the celebration, as this year, just like a year ago, everything about the Ukrainian people – the ones protecting Europe from the yoke of Ruscism – feels even more special.

Alphonsine Williams and friends wearing vyshyvankas at an NFL event What Is Vyshyvanka Day?As has already been mentioned, Vyshyvanka Day is celebrated every third Thursday of May. This year, it will be May 18. An international holiday celebrated in more than 60 countries around the world, including the United States, Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and France, Vyshyvanka Day aims to preserve Ukrainian folk traditions. Some might say the holiday boils down to specifically maintaining the tradition of creating and wearing ethnic embroidered clothes. Nonetheless, the value of vyshyvanka’s symbolism is way more far-reaching. The people of Ukraine consider vyshyvanka as one of the major totems of their national identity.Yet, for decades, everything that’s originally Ukrainian has been forbidden and blocked by the Soviets. The first years of Ukraine’s independence tolled on the nation’s civil consciousness with the economic hardships of the post-colonial aftermath. It was in 2006 that a Chernivtsi National University Student, Lesia Voroniuk came up with an idea to gather together with her fellow students on a chosen day and wear their vyshyvankas to the university. Their first try was a success: several dozen students and faculty members supported the idea; at least, they thought it was a success until they saw how the following year’s Vyshyvanka Day turned out.During 2007-2011, the holiday grew to a national level. The Ukrainian diaspora from all around the world joined. When choosing the date for the celebration, Lesia said that they had intentionally chosen a weekday to strike on the message that vyshyvanka is an integral component of modern Ukrainians’ lives and not a relic from the past. In 2011, on the holiday’s fifth anniversary, the participants set a Guinness World Record for “the largest number of people dressed in embroidered shirts and gathered in one place” – more than 4,000 people in their vyshyvankas gathered on the central square of the city of Chernivtsi. They even prepared one for the city’s university main building by sewing a gigantic (4 × 10 meters) vyshyvanka.In 2015, after the start of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of the Donbas and annexation of Crimea, Vyshyvanka Day was celebrated under the slogan: “Give a vyshyvanka to a defender.” As already mentioned, vyshyvanka is known as a talisman that protects people from anything bad that might happen to them, and the campaign above was meant to raise the Ukrainian army’s fighting spirit. That year, it was for the first time that more than 50 countries joined the celebrations. Eight years later, and almost 1.5 years into the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, vyshyvanka remains the unchanging symbol of the Ukrainian identity. During one of his latest addresses to the nation, President Volodymyr Zelenskyi wore a black vyshyvanka with green and olive embroidery featuring the emblem of the Kyivan Prince, Sviatoslav the Brave. Today’s Ukrainian Special Operations Forces use it as their symbol as well. Time passes, but vyshyvankas keep on reflecting and preserving everything that happens in Ukraine’s rich and yet swerving history.Closing RemarksVyshyvanka is more than just clothes for Ukrainians. As a cumulative term, vyshyvanka is a repository of nations codes, libraries, and frameworks, which together represent the Ukrainian culture in its magnitude of an already accomplished project; a project that happened and has a bright future in front of itself. While the Internet might still be full of ludicrous Russian propaganda’s narratives about the Ukrainians being the descendants of the Russians – cultural, political, economic – the very concept of vyshyvanka (so tiny in the greater scheme of things and yet so powerful in terms of establishing historical justice) eradicates this semantic nonsense. At the end of the day, the Kyivan Rus, was called Kyivan and not Moscowite for a reason. It is a pride for us to be able to say that our colleagues in Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, are joining the celebration, as this year, just like a year ago, everything about the Ukrainian people – the ones protecting Europe from the yoke of Ruscism – feels even more special.